Lightning protection technology is a big part of why air travel in 2020 is incredibly safe.

Yet, it wasn’t always this way.

Safety has improved in every facet of aviation, even as engineers continue to push the limits of what planes can do.

The History of Lighting Protection

Lightning protection technology has come a very long way. Humankind is now minimally affected by this very dangerous, destructive natural force.

Today, we build higher than ever, fly more than ever, and have seen our population grow to over 7.8 billion people.

Yet, buildings rarely get destroyed or set ablaze by lightning strikes. Planes suffer only minor, occasional damage and are at virtually no risk of being downed due to a strike. People know how to protect themselves in thunderstorms and mitigate their personal risk in a of being struck by direct or ground current.

It didn’t used to be this way.

Lightning: Destructive Tool of Zeus?

There was a time when it was believed that lightning bolts were thrown down at us by the Greek God Zeus.

A few millennia later in the 1740s, humankind till didn’t understand lightning–where it came from, why it occurred, and how to protect themselves from it.

It would strike buildings and damage or destroy them.

People would take cover under trees in a thunderstorm and be killed, not realizing the very shelter they sought made them more at risk.

Advances in knowledge gave ordinary people tools to fight back against the heavens. Lightning protection technology–today thought of as physical devices–was first the mere understanding of how to protect ourselves from it.

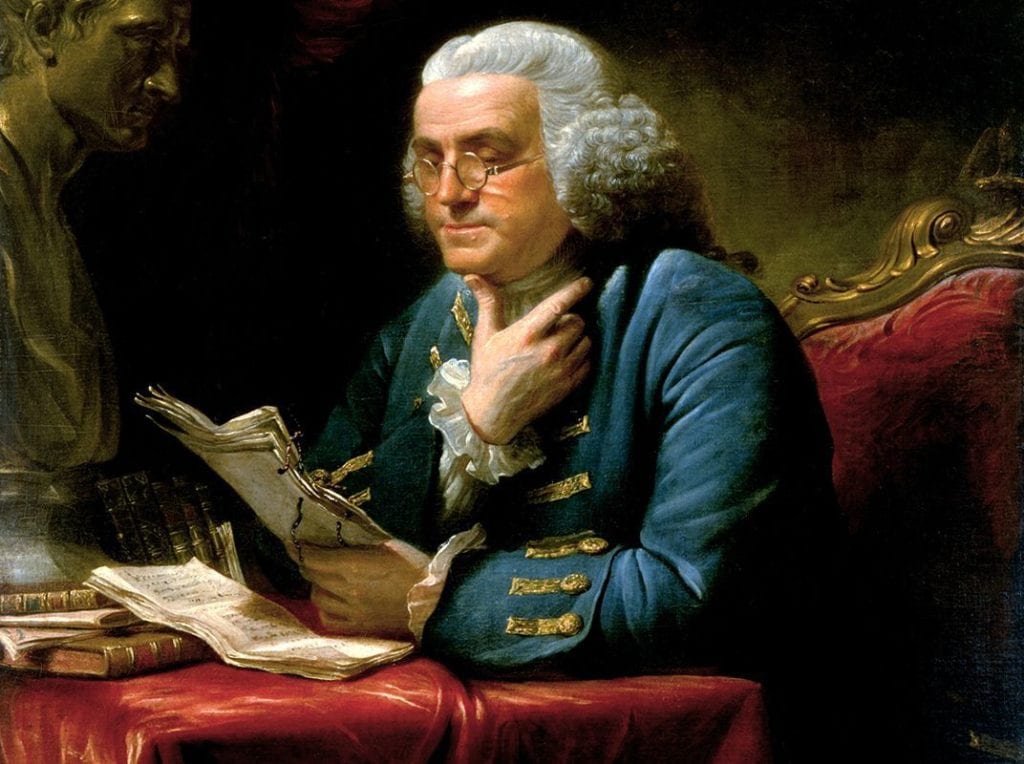

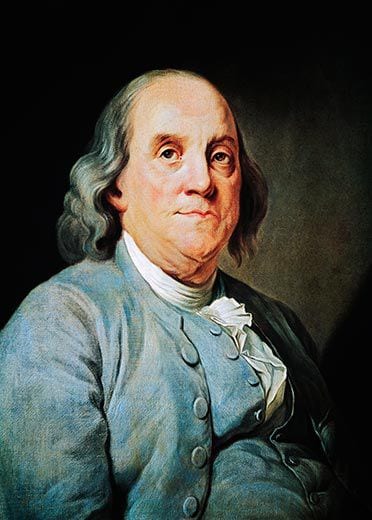

1752: Benjamin Franklin, Inventor of Lightning Protection Technology

The scientific achievements of Benjamin Franklin set in motion our ability to tame electricity in all forms. What would eventually protect passenger airlines crammed full of families traveling the world, started with the lowly lightning rod.

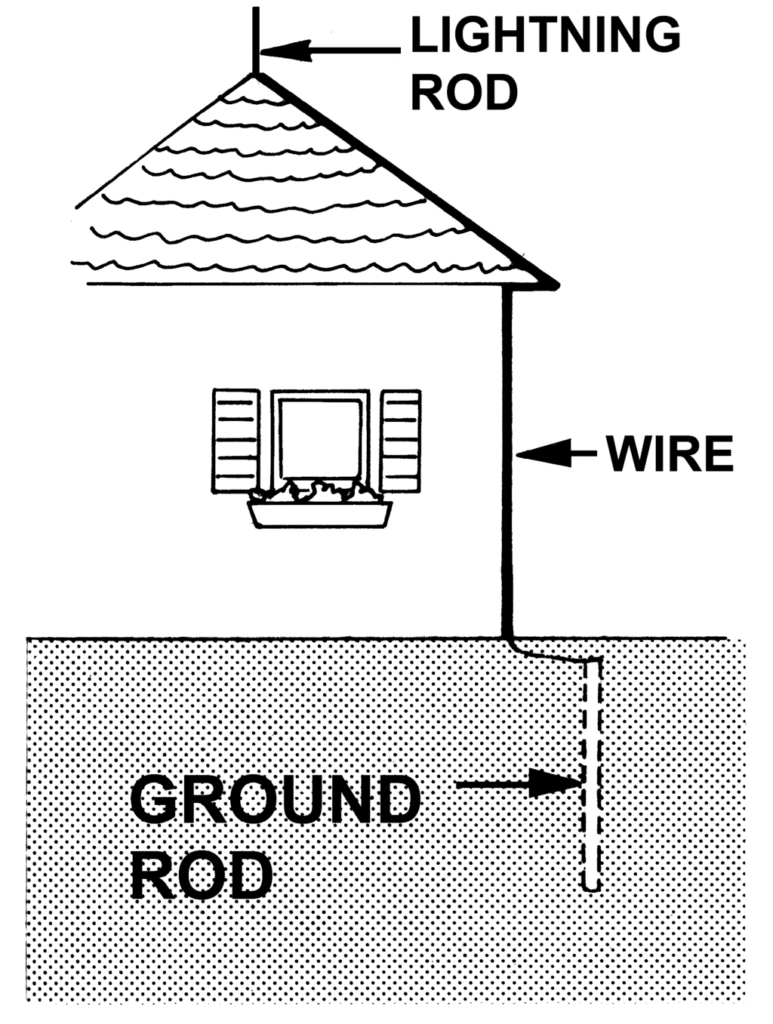

In the late 1740s, Benjamin Franklin had conducted a series of experiments leading him to the conclusion that pointed metal rods, installed above buildings, could attract lightning.

By attaching a long conductor to the rod, which in turn led to a spike driven 10 feet into the ground, the lightning could be safely diverted into the ground instead of damaging buildings.

In 1752, his experiment had been shared abroad and re-tested in France with great success.

The Invention of the Lightning Rod Was a BIG Deal

This invention of the lightning rod feels…humdrum by today’s standards.

Electricity has been a part of the modern human life for so long now that it’s been largely reduced to the life of a caged animal. Sure, lightning still dances in the sky as it pleases. Yet most it is produced, harnessed, controlled, dispensed and metered like the modern utility that it is.

Franklin’s Understanding of Lightning Earned him Worldwide Fame

Benjamin Franklin’s invention was incredibly profound for a reason bigger than the mere homes and churches it would protect.

To be clear, his fame was profound.

He was known all over the world in a time when it took months to cross an ocean by ship–a world without telephones, email or the internet.

His fame and celebrity expanded across oceans, continents and even warring countries.

Franklin vaulted to worldwide fame because he managed to tame a phenomenon that was thought to have been the will of the Gods for thousands of years.

He caught Zeus’ mighty lightning bolt.

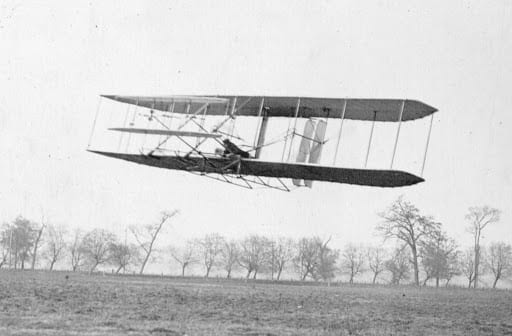

When The Airplane Was Invented, It Too Needed Protection

While Franklin’s invention and insights about the behavior of lightning undoubtedly saved countless houses and lives, a new question emerged with the invention of the airplane:

Would airplanes get struck by lightning?

For a while, we simply didn’t know.

Then, the facts began to emerge that yes, in fact, airships, planes, and helicopters were all very likely to get struck by lightning. Statistics today show that every commercial aircraft gets struck about once per year.

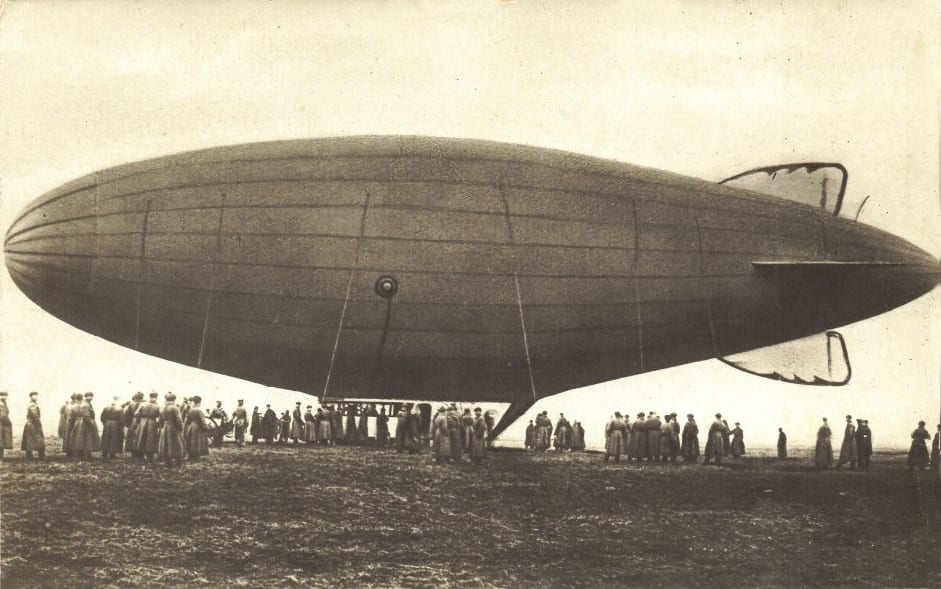

In 1915, A German Airship Was Destroyed By a Lightning Strike

A German navy airship was downed by a lightning strike in 1915, taking with it all 19 crew members.

This documented disaster put to bed the idea that aircraft weren’t–or couldn’t–crash due to a lightning strike. However, 15 years later, aviation experts were still denying that planes were being struck.

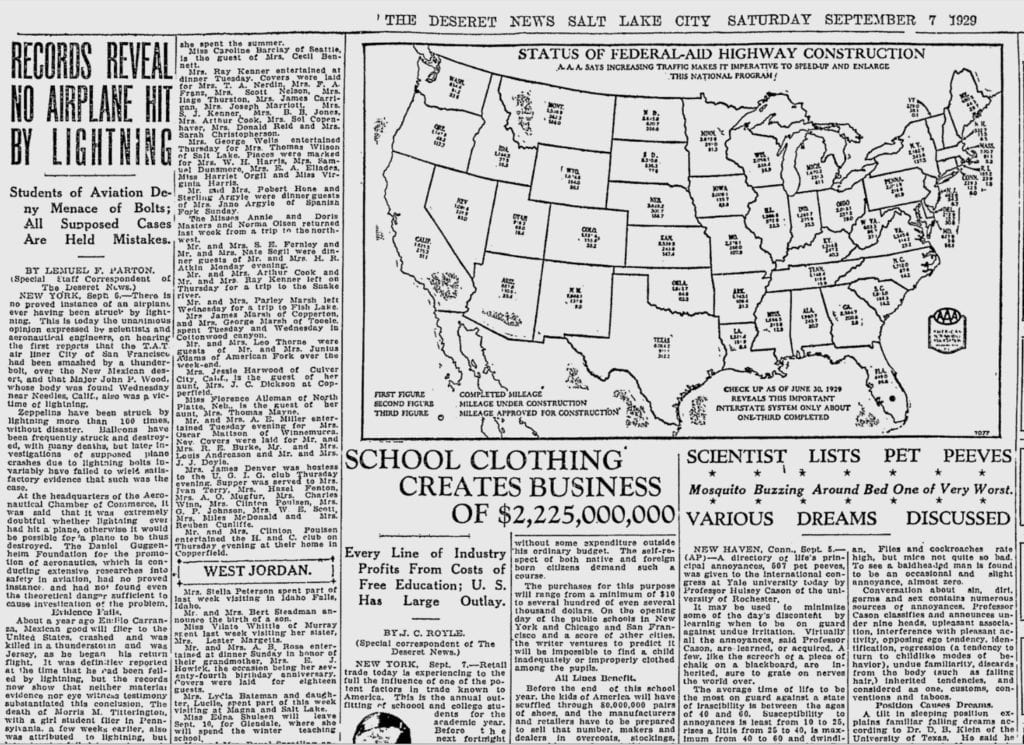

1929: First Known Case of An Airplane Being Struck By Lightning…or Was It?

In 1929, Lemuel F. Parton wrote an article that reported on whether or not airplanes had ever been hit by lightning. His article included extensive commentary from experts claiming that no airplane had ever been hit by lightning.

The article conceded that airships–including the known 1915 disaster in Germany–were confirmed to have been struck many times, but never an airplane.

Reading the article today, it’s not clear whether the airplane crash in question in the 1929 article was, in fact, downed by lightning.

Yet, it is clear–knowing what we know about the frequency of aircraft lightning strikes–that airplanes and all types of aircraft were susceptible to strikes as soon as they took to the sky. Flying in and around electrically charged storm clouds all but assures that some percentage of planes will be struck, because the planes themselves trigger the strikes.

A 1963 Report on Lightning Strikes on Aircraft Over a Two-Year Period

In the 1963 article by Lt. Colonel Ferd J. Curtis titled How Dangerous is Lightning? 66 reported electrical incidences are analyzed. These incidences represent a combination of lightning strikes and static electrical discharges.

Of the 66 reported lightning strikes that were analyzed, the following was found:

- 22 radomes were damaged.

- Two of the 22 had their radar systems damaged to the point where they became inoperable.

- Systems malfunction occurred in 12 incidences.

- 34 of the 66 strikes occurred in altitudes between 5000-10,000 feet

- 29 of the 66 strikes occurred in the spring, nearly triple the rate of any other season.

- One major accident was reported, in which a F-102 pilot ejected after experiencing control difficulty following a lightning strike. The pilot witnessed a ball of fire and ejected shortly thereafter.

Overall, the article concludes that though damage to aircraft is common in lightning strikes, they are not typically dangerous. Lightning protection technology was still very rudimentary at the time, but even then, most strikes weren’t downing planes.

Though the author concedes that lightning strikes—which are often accompanied by a loud BANG and bright flash—are among the most startling things a pilot can encounter, major accidents were rare.

December, 1963: Pan Am Flight 214 Crashes Due to a Lightning Strike

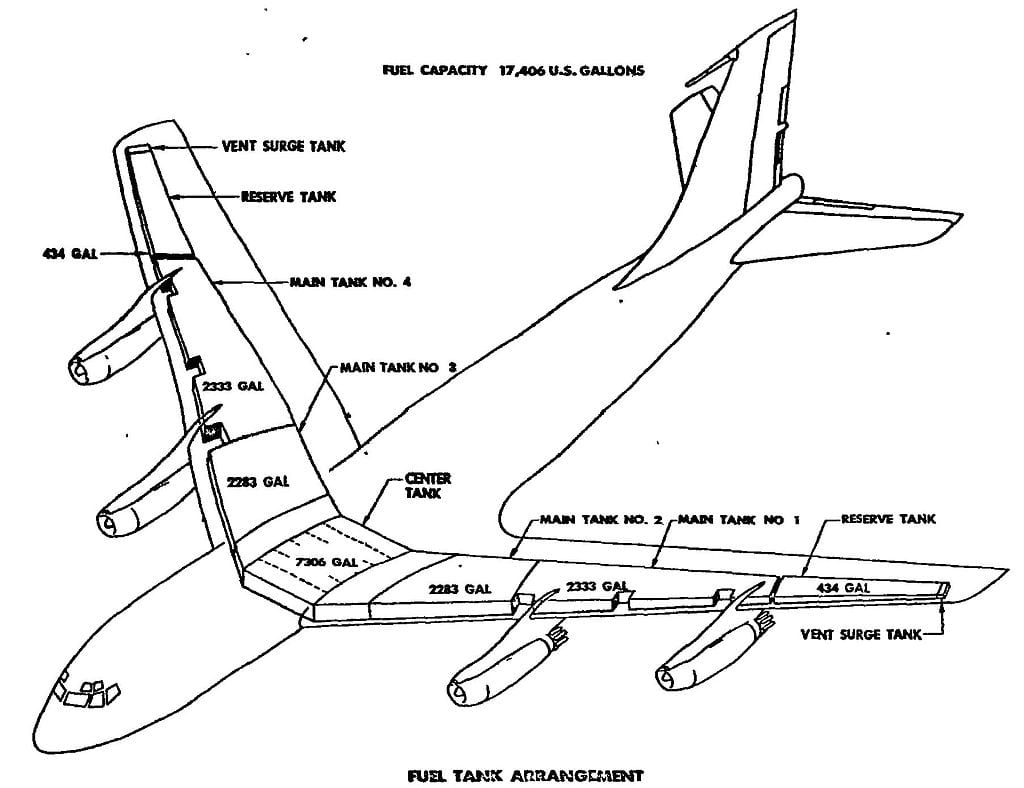

Flying from San Juan, Puerto Rico, to Baltimore, Maryland, Pan Am Flight 214 crashed on December 8, 1963. All 81 passengers and crew were killed after a lightning strike downed the Boeing 707 jet.

It was determined early in the investigation that an explosion blew off the wing tip, as wing tip parts were found miles from the main crash scene with signs of an internal explosive force.

But, investigators at first were unsure what caused such an explosion.

After the discovery of lightning strike marks on another section of the wing, the eventual conclusion was that a lightning strike caused fuel vapors within reserve tank #1 to ignite, exploding and breaking the wing apart.

Though this phenomenon of fuel vapor ignition was addressed, there was still little regulation in place for enforcement of new safety rules.

30 years later, another plane would explode midair shortly after takeoff due to the same vapor ignition problem.

May 1965: A Lightning Strike Sets an Air Force C-130 on Fire

There was a report of a C-130 plane taking a lightning strike, which punctured an eight-inch hole in the nose radome. Making the situation even more dangerous, the radar equipment was badly damaged and a pylon was set on fire, which burned until the plane landed.

This was a terrifying experience for the pilots, to say the least. To watch their aircraft burn after a lightning strike, with reduced radar visibility must have made for one scary landing.

November 1969: Apollo 12 Spaceship is Struck by Lightning TWICE During Launch

Everything changed when the Apollo 12 was struck by lightning not once, but twice on launch.

What were the odds, right?

Researchers would come to learn that it wasn’t a coincidence at all.

Space shuttles and aircraft both cause lightning strikes.

After the lightning strikes to the Apollo 12, the sentiment from leadership was essentially, figure out why this happened and make sure it never happens again.

Extensive research was thus conducted by a NASA-commissioned team. Their conclusion on the Apollo 12 near-disaster? Rockets (and other large metal objects) can cause lightning strikes–it was not a coincidence.

Planes are Like Big Lightning Rods

As a plane (or any type of aircraft) flies through the atmosphere, it essentially acts like a moving lightning rod.

Electrical charge builds up on an object two ways: through friction or electrical fields.

Planes fly through electrified clouds and become charge from both the electric fields and from collisions with tiny ice particles in the clouds.

Positive charge accumulates on an extremity of the aircraft (nose or tail or wingtip), and slowly increases until it becomes significant enough to create a powerful lightning streamer. The positive streamer from the aircraft travels towards the negative charge center (either a cloud or ground).

While the positive leader moves away from the aircraft, a negative leader forms on the opposite side of the aircraft and begins to propagate away from the aircraft. Over several milliseconds, the positive and negative leaders from the aircraft reach the electrical charge stored in the clouds and create a lightning strike.

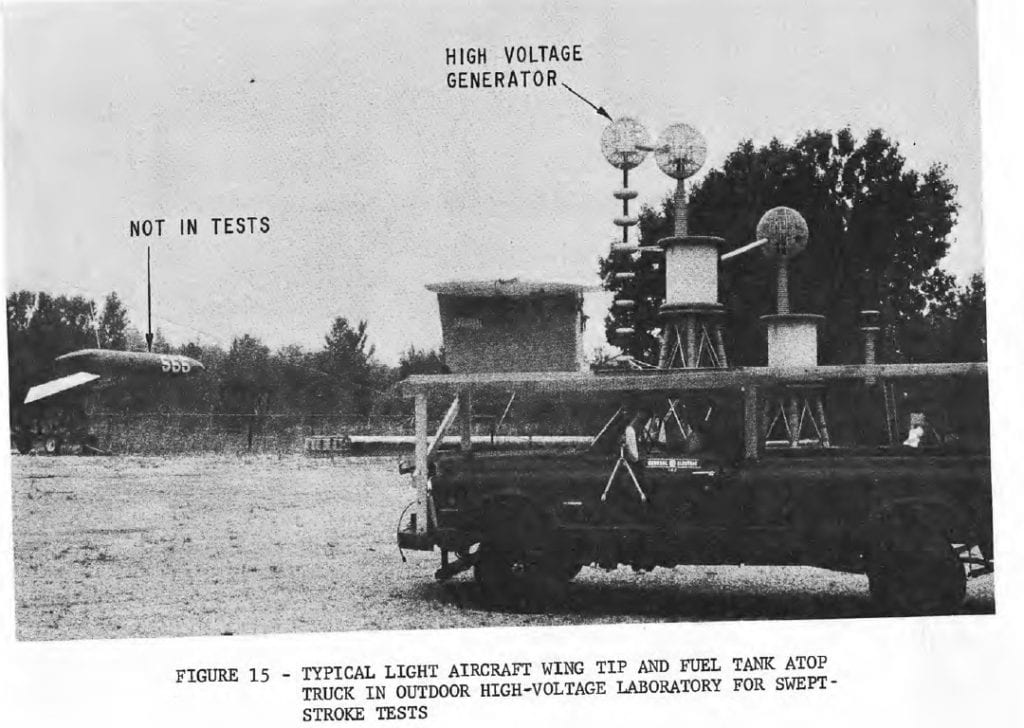

In the 1960s and 1970s, the handful of major accidents (including the Apollo 12) were enough to bring the issue of lightning protection into the spotlight. Aviation engineers got to work devising better systems to mitigate risks to fuel tanks, radar equipment and other vital systems. Testing systems had to be devised to first understand lightning better.

Accidents would continue, but engineers and scientists would continue to conduct deep analysis and improve safety after each one.

December, 1971: Lansa Flight 580 Crashes Due to Lightning Strike

There is not a tremendous about known about the circumstances of the crash of LANSA Flight 508.

The crash report states that the plane flew through severe thunderstorms and turbulence before taking a lightning strike to the wing.

The right wing caught fire and broke off, along with a section of the left wing. Then, the Lockheed L-188A Electra turboprop went down into the mountains.

85 of the 86 passengers aboard Lansa flight 508 were killed.

One passenger–a 17-year-old girl, Juliane Koepcke, miraculously survived the crash and wandered through the Amazon jungle for 10 days before being found by locals and rescued.

How Do Passengers Not Get Electrocuted When a Plane is Struck?

It’s a known fact that if a person is close to an object that gets struck by lightning–such as a tree–the electricity flowing into the ground can cause electrocution.

This flow of ground current is often deadly to livestock and other animals with a wide leg base, and the ground current enters the point of ground contact closest to the strike and flows out the farthest point of ground contact. Humans can also be injured or killed by ground current, but injuries are less often fatal because of our narrower leg stance.

Knowing this, how are people in airplanes, helicopters or airships not electrocuted? Doesn’t the electricity in an aircraft lightning strike behave in the same deadly way?

People Inside an Aircraft Are Safe Because of the Faraday Principle

The Faraday Cage shields those inside it from electrical fields. As electricity flows into the cage, it’s distributed around it rather than arcing through it. The metal skin of an aircraft acts like a big Faraday Cage when struck by lightning–the current is distributed throughout the skin, cancelling out electrical charge in the middle, protecting those inside it.

There’s no reason to fear personal injury from the lightning itself when flying in any type of aircraft because of this phenomenon. As a flying Faraday Cage, the occupants are safe…at least from the electricity itself.

Report for NASA in 1981 on Two Air Force Jets Struck By Lightning

A NASA Report from 1981 showed two Air Force F-106A aircraft were struck by lightning in the same storm. One plane was struck twice, while the other was struck once.

There was extensive damage to a pitot tube, which was the initial attachment point of the lightning strike. None of the planes’ avionics were damaged, however, nor was the radome punctured.

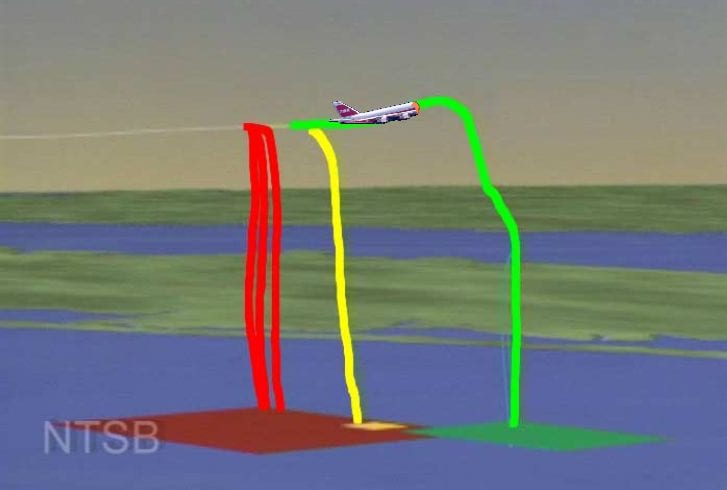

July, 1996: TWA Flight 800 Explodes Over The Atlantic Ocean

Just 12 minutes after takeoff, an explosion and crash into the ocean was reported by other pilots in the sky above the Atlantic Ocean. The explosion was TWA 800’s final flight, taking with it all 230 passengers and crew.

Though this tragic accident was not caused by a lightning strike, it had wide-ranging implications for lightning protection systems in aircraft.

The cause was later determined to be a spark–likely from a short-circuit–that ignited fumes in an empty fuel tank in the center of the plane.

The explosion reinvigorated the discussion of protecting planes from two sources of ignition:

- Combustible fuel vapor found in fuel tanks

- Sparks caused by electrical arcing

Could a Lightning Strike Cause The Same Electrical Arc that Cause TWA 800 to Explode?

Yes, it could.

This realization, though not new (planes had mysteriously exploded occasionally since their creation), was still scary.

This public fear and outcry furthered technology and advancements in lightning protection systems.

In the period from 1999-2002, as a result of TWA 800’s explosion, the FAA and other governing bodies mandated that plane manufacturers demonstrate that under no circumstances could fuel vapors within empty or partially-empty tanks ignite.

In essence, aircraft operators had to demonstrate that lightning could not possibly create an arc on a plane in the way that occurred on TWA 800.

Spark Gaps Were Found and Closed

All potential ignition sources in the fuel tanks had to be eliminated, with a combination of improved designs, special sealants and electrical insulation.

Fuel Tanks Were Filled with Inert Gas

Systems to inject nitrogen gas into fuel tanks became mandatory, which greatly improved safety and protection from explosion. Though inert gas technology was not new, advancements in the system hardware and reliability made their installations in a wide variety of aircraft possible.

1977: Lightning Technologies Inc Writes Lightning Protection Regulations

As a result of the Apollo 12 lightning strikes and the development efforts for the Space Shuttle, NASA commissioned a lightning protection design handbook by Frank Fisher and Andy Plumer, who worked at General Electric in Pittsfield, MA.

The design handbook and the subsequent industry guidance Plumer and Fisher devised were instrumental in keeping millions of air passengers safe from lightning.

The composite parts on an aircraft–such as a radome–are the most susceptible because if lightning energy passes through them, it will burn or puncture holes on its way to a better conductor.

Today: Safe, But Never Without Risk

In July, 2019, a Russian Superjet-100 was struck by lightning as it took off. The pilot, making an error in judgment, turned the plane around and attempted to land after experiencing a slight loss of control.

The plane, too heavy with fuel, bounced on the runway and burst into flames. 41 passengers in the rear of the plane were killed, while 37 passengers escaped.

Though the jet in question was modern and equipped with approved lightning protection, it was still affected by the strike.

Though aircraft have never been safer, air travel is still not without risk.

Learn More About Lightning Protection Technology

At Weather Guard Lightning Tech, we’re obsessed with aircraft lightning safety.

We’re continue to improve on our industry-best lightning protection technology, because we want everyone to take off and touch down safely.

Check out a few more of our educational resources below:

- The Weather Guard YouTube Channel

- Our Free Lightning Protection Video Series for Radome Engineers

Lightning Protection Technology FAQ

Have a question or comment? Leave one and we’ll answer it.